Caroline Doris Ketelbey (1896-1990)

Doris Ketelbey was the first woman to hold a long-term position as member of staff in History at St Andrews [read about other early women staff]. She was appointed as an Assistant Lecturer in 1935; and retired as Senior Lecturer in 1958. Her academic interests ranged from modern European history and international relations to the history of the British empire and its colonies; in her retirement, she devoted herself to local Fife history. Her full name was Caroline Doris Mabel Keteley: she appears to have preferred the name ‘Doris’ for most of her life, but she began using ‘Caroline’ or ‘C.D.M.’ on her published works from the 1950s.

Childhood and education

Our information on her early life comes from the substantial history of the Ketelbey family that Doris Ketelbey compiled in her retirement: its two typescript volumes are now in the University of St Andrews library. She traced the family back to mediaeval times – but by the time Doris herself was born, her branch of the family was based in Birmingham. Her father was an art teacher at the School of Design, and had prospered sufficiently to move his family to a house with a garden in an affluent suburb, where Doris was born in 1896.

Doris was the baby of the family: her four surviving siblings had been born between 1873 and 1883. Despite the age gap, her siblings are recorded as still living in the family home in the 1901 census. The eldest, Florence, was a dressmaker; she had lost her hearing due to a bout of scarlet fever, leading the whole family to learn sign language. Albert had trained at music college in London, and would go on to become a successful composer of light music in the interwar years. Edith was a clerk, and Harold was trying to forge a career as a violinist. In contrast, Doris described her ‘inclination’ as being ‘towards a more conventional academic line’.

She benefited both from her father’s library, and from the expanding opportunities for secondary and higher education for women. She recalled that, ‘the only restrictions’ her father placed upon her use of his library ‘was upon his medical books which were put out of my reach, and, oddly enough, Jane Eyre which, I imagine, he thought might give me too early a taste for the romantic’. With such musical siblings, it is no surprise that she learned piano, but she claimed to have ‘read many a Dickens novel under cover of the major and minor scales’.

Doris attended King Edward’s Grammar School, 1906-14. Of her ambitions to continue her education, her father apparently said that, ‘Times are changing and if she wants to go to a University let her go’. Writing sixty years later, Doris commented, ‘I have never forgotten his remark nor ceased to be grateful for his indulgence.’

She began to study for an MA at the University of Birmingham in 1914. In summer 1917, she was awarded one of two research scholarships by the University. Her subsequent interests in modern political history, and particularly what would now be called ‘international relations’, may have their roots in her MA thesis: A comparative study of federation in the United States since the declaration of independence, in Switzerland since the thirteenth century and in Germany since 1866, with reference to federation in the British Empire.

She spent a year (1918-19) at Somerville College, Oxford, but we do not yet know what she did there.

School teaching, authorship and editing in the 1920s

After Oxford, Doris Ketelbey accepted a teaching position at St Leonard’s School, in St Andrews, where she worked until 1927. St Leonard’s was then a school for girls, and there were close links with the University – not just because the school educated girls for the University, but through the careers of women who moved between roles in the school and the University. (This movement between school teaching and academia was not uncommon in the first decades of the twentieth century: there were so few university roles available to women that many of those who were later appointed had spent at least some time as school teachers.) We look forward to finding out more about her time at St Leonard’s.

In the mid-1920s, the London educational publisher Harrap was issuing a series of ‘Readings from the Great Historians’. This was the beginning of Ketelbey’s publishing career. While working at St Leonard’s, she compiled two volumes on European history for Harrap: the first covered the period from ‘the fall of Rome to the eve of the French revolution’ and appeared in 1924; it was followed in 1926 by a volume from ‘the eve of the French revolution to the eve of the Great War’. We do not currently know how Ketelbey got the commission for these volumes; but the fact that the volume on seventeenth-century British history had been compiled by John W. Williams, then a lecturer in modern history at the University of St Andrews, suggests a possible connection.

After Ketelbey left St Leonard’s in 1927, she appears to have been working on the book that became her biggest success: A History of Modern Times: from 1789 to the present day was published by Harrap in 1929. It was a textbook for schools, though there is some evidence it was also used in some universities for the early stages of a History degree. It went through multiple reprintings, and at least five editions, the last in the 1970s. In 1963, it would be translated into Hindi, specifically for use in schools in India.

In 1930-31, Ketelbey says that she worked for press baron Lord Beaverbrook; it is not clear what this role involved.

In 1931-32, she gained her first appointment in a university, as assistant to James Eadie Todd, professor of modern history at Queen’s University Belfast. This was, however, only a temporary appointment – as these assistantships usually were.

Her whereabouts in the next few years are unclear, but her mother died in 1934 and it is possible she was involved in nursing for some period. In December 1932, The Scotsman reported that Ketelbey had been appointed as an interim lecturer at the University of St Andrews, to replace William Burn (the lecturer in American and Colonial History) while he spent a year in the United States on a Rockefeller Fellowship. However, it is unclear whether this appointment did in fact take place: Ketelbey does not mention it in her later recollections, and we have found not record of it in the University records.

Assistant Lecturer at St Andrews, 1935-45

In 1935, at the age of 39 years, Ketelbey definitely returned to St Andrews, to a role as Assistant Lecturer in the department of Modern History. At this point, ‘modern history’ meant everything that was not ‘ancient history’; it was not until 1955 that a separate department of ‘mediaeval history’ was created.

Formally, Ketelbey was ‘Assistant to the Professor of History’. This was John W. Williams, whom Ketelbey may have known since they both worked with Harrap a decade earlier. The only other History staff were William Burn, now back from the US; and Ronald Cant, the lecturer in Scottish and Mediaeval History.

The role of ‘Assistant’ or ‘Assistant Lecturer’ was a precarious one, depending on annual renewals (See our posts on The Assistant in the Early 20th Century and Assistantship in the Mid-to-Late 20th Century). There was no guarantee of eventual appointment as ‘Lecturer’, and some women (and some men) remained ‘assistants’ for a decade or more. And even lecturers were subject to regular renewals; it was only ‘the professor’ in each subject who had long-term security of employment. Ketelbey remained an ‘assistant’ until 1945.

We do not yet know much about Ketelbey’s teaching in this period (though see our post on ‘A day in the life, 1930s’ for some sense of the student experience).

On arrival in St Andrews, Ketelbey seems to have thrown herself (back) into the local community. For instance, she wrote letters to the local paper, and gave talks in the late 1930s on women’s position in Nazi Germany to the St Andrews Christian Institute, the Broughty Ferry Women Citizens Association, and the Workers Educational Association in Dundee. She was also working with the BBC: in 1938, teaching Scottish History to school children via the radio. [She was already a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society by 1938.]

The Second World War affected both students and staff at the University. The absence of male staff on war work led to the hiring of additional assistants: by July 1942, Ketelbey had been joined by a second assistant in History. The University offered short courses through the Air Ministry Training Scheme, and so, in 1944, Ketelbey was lecturing trainee RAF personnel on History.

Earlier in the war, she had contributed a 24-page pamphlet on The Growth of the British Empire to a series commissioned in response to a request to improve ‘adult education among members of H.M. Forces’. Apparently, ‘Polish and other Allied troops’ sought more information about ‘Britain and its institutions’. These pamphlets were distributed amongst allied units, and ‘Education officers in our own units’ are recorded as finding them particularly useful.

In December 1942, perhaps emboldened by being no longer the most junior member of the department, Ketelbey petitioned the University Court for promotion to Lecturer, ‘on account of her long service’. Despite the ‘approval and consent’ of Professor John Williams, her request was denied.

Her salary at this point was just £300p.a. In 1943, she would receive a pay rise of £25 plus a war bonus of £25 – but still no change of status.

Lecturer at St Andrews, Professor in the Gold Coast, 1945-58

It was not until 1945, after eleven years in the department, that Ketelbey was promoted to Lecturer. From this point, her responsibilities within the department and the University began to grow. In 1946, she was appointed as assistant advisor of studies, a position which she held intermittently for over a decade. When Lorna Walker arrived in St Andrews as an undergraduate in 1948, it was ‘Miss Ketelbey’ who advised her on her subject choices. In 1948, Ketelbey became one of the Preliminary Examiners in History; and the following year, she represented the University at a conference on the teaching of international relations held at the London School of Economics. She had also been appointed to the council of the Scottish History Association in 1946.

1950 was a significant year for Ketelbey:

Due to a change in academic employment contracts, she (and 33 others in the University) moved on to a 5-year-contract, a vast improvement from the annually-renewed contracts which dominated the lives of professional academics working in the first half of the century.

And, in the same year, Ketelbey was ‘invited by the Council of the University College of the Gold Coast [now the University of Ghana] to accept an appointment as visiting Professor at the University College to organise the Department of History there and to arrange the syllabus in consultation with the appropriate authorities of the University of London’. This required her to take a leave-of-absence from St Andrews for two terms: Professor Williams gave his ‘reluctant consent’, and the University Court authorised her absence for six months from October 1950. The negotiations for her temporary replacement reveal that she was now on a salary of £850. To learn more about Ketelbey’s time in Ghana – where she was recognised as a ‘professor’ for the only time in her career – read our article linked here.

Ketelbey’s visit to the Gold Coast extended her long-standing interest in the relations between nation states. In 1952, the University again chose her as its representative to the LSE Conference on the Teaching of International Relations, explaining that ‘most of the agenda is concerned with the problems of colonial territories in which she has a special interest after her visit to the Gold Coast’. International Relations would not be taught as a separate subject at St Andrews until 1978 (and the department of IR was only created in 1990), but Ketelbey may have been incorporating her interests in International Relations into her teaching of Modern History long before then.

As Ketelbey’s profile grew, she once more sought recognition: in June 1951, she requested that the University court consider ‘advancing her to Lectureship Grade I’ (from her current Grade II). This was refused in 1951, but granted the following year: her salary immediately increased to £900 p.a., and would increase by annual £50 increments to £1,100.

In 1955, the University decided to promote three of its long-serving women lecturers to Senior Lecturer (with effect from October 1956), and Ketelbey was one. All three women were entering their sixties, and had been employed by the University since the interwar period. At a time when each department had only one Professor (‘the professor’), and Readers were rarely used, Senior Lecturer was the most senior position available to most academics.

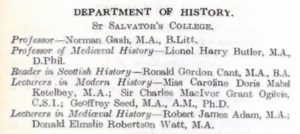

The department of History in the mid-1950s looked quite different from the days when Ketelbey was one of four staff. There had been an influx of new staff just after the war; and in 1954/55, professor John Williams had retired. The University made two appointments to replace him: Norman Gash as Professor of Modern History; Lionel Butler as Professor of Mediaeval History. For St Andrews, this was the origin of two separate History departments: in 1955, the two new professors were supported by three lecturers in Modern History (including Ketelbey), and two lecturers in Mediaeval History; with long-serving Ronald Cant now listed as Reader in Scottish History.

Of the eight St Andrews historians in 1955, Ketelbey was the only woman. A year later, however, Dr Margaret Lambert was appointed to a lectureship. Given Lambert’s research interests in modern European history (especially Germany), her affiliation with the LSE, and her previous work with the BBC, it is intriguing to speculate on whether Ketelbey and Lambert already knew each other. Lambert was ten years younger than Ketelbey, and unlike her, had gained a PhD – something that was true of only one other lecturer, and one of the professors, at St Andrews.

Retirement, 1958-1990

On the 30th of September 1958, at age 62, Ketelbey retired. She cited ‘health reasons’ for this decision, having apparently not yet reached the age limit. Other members of the University who retired that year were presented with gifts (including a radio set, a clock, and a cheque), but there is no record of a presentation for Miss Ketelbey.

She continued to live in St Andrews – at 18 Queen’s Gardens – until her death in 1990. She clearly remained intellectually active for much of that time. Her immediate retirement project was a history of the local Fife paper mill company, Tullis Russell, to celebrate its 150th anniversary. Her account began appearing in articles in the Rothmill Quarterly from 1959, and then in book form in 1967. The introduction to the book described it as ‘a masterpiece of historical research, covering not merely the history of the Firm, but of Fife Industry, Fife Society and Fife History’ (Tullis Russell, 1967, p.v).

In the 1970s, she became interested in her own family history, perhaps stimulated by a wave of interest in her (deceased) brother Albert, the composer on the occasion of the centenary of his 1875 birth. Between 1975 and 1982, she compiled two substantial typescript volumes of Ketelbey family history, supposedly as a way of using her skills as ‘a professional historian’ for the benefit of her nephews and nieces (including her brother Harold’s family, in South Africa).

In December of 1990, Caroline Doris Mabel Ketelbey passed away, aged 94 years. She is buried in St Andrews’ Western Cemetery.

Ketelbey lived such a long life that her role as a pioneering woman academic seems to have been forgotten at St Andrews. Back in 1960, she had been asked to do some temporary teaching, after Margaret Lambert resigned mid-way through the academic year. It is not clear whether she did this or not, but the invitation suggests that her skills were still recognised and valued by the colleagues she had, until recently, worked alongside. By the time she died three decades later, however, the Alumnus Chronicle struggled to find much to say: ‘A much respected member of staff, her companionship and wise counsel will be missed by all who knew her’. It described her only as ‘Lecturer’, thus denying the recognition of her hard-won promotion to Senior Lecturer. By the time Sarah Pearsall and Emma Hart were appointed to lectureships in Modern History in the early 2000s, they – and their colleagues – believed that they were the first women in Modern History at St Andrews.

Institutional memory, and that sparse obituary, have not done justice to a well-respected historian. She had a long and successful career as a teacher, researcher and author, as evidenced by her repeatedly reprinted textbook, her roles representing the University, and her promotion to Senior Lecturer. Her engagement with the local community in Fife, and with the new university in Ghana, show how she used her historical expertise to think about the contemporary challenges of wartime and postwar Europe and decolonisation. We hope that our research into Ketelbey has done her and her remarkable career justice.

University of St Andrews Court Minutes, 1936-1960

University of St Andrews Alumnus Chronicle (1958 and 1991)

Ketelbey, D.M. A History of Modern Times: from 1789 to the present day (Harrap, 1929)

Ketelbey, C.D.M. Tullis Russell: the history of Robert Tullis and Co and Russell Tullis and Co Ltd; 1809-1959 , (Markinch, 1967)

Ketelbey, C.D.M., ‘In search of Ketelbeys’ (2 vols, unpublished, compiled c1975-82, held in University of St Andrews Library)

—

The first version of this life story was written in July 2021 by Libby Hawken and Jemima Askew. Jemima recently graduated from St Andrews with a degree in Psychology, and Libby was then entering her fourth year of an MA in History. The life story was revised and updated by Aileen Fyfe in April 2022. With thanks to Morag Fyfe for genealogical and historic newspaper research.

Cite as: Aileen Fyfe, Libby Hawken and Jemima Askew, ‘Doris Ketelbey MA, FRHistS 1896-1990’ (2021-22) Women Historians of St Andrews https://women-historians.wp.st-andrews.ac.uk/2022/04/05/doris-ketelbey-ma-frhists-an-impressive-career/

For those who need to see sources, a fully-footnoted version of this life story is available: Doris Ketelbey life story_v2. [PDF]