Past History Papers: 1970s

Once we reach the 1970s, we finally start to see more diversity in what was being taught and examined in History at St Andrews. The examinations are still being split into general papers on historical period, but we finally start to see what would be a recognisable sight to honours history students today: small and specific modules that would have taken by a small group of students. There is a clear leap taken from the exams of the 1950s, both in the number of papers that were recorded and in the range of specific historical knowledge that was on offer.

One of the biggest differences was in the geographical range of information that was being tested on. In previous papers the history being taught was limited mostly to Western Europe, but these papers offer a lot more. In the 1975 Medieval European History paper there are questions, not only on Western Europe and the British Isles but also on the Byzantine Empire and Jerusalem. This divergence from the typical questions that were asked is reflected in the Modern History papers, where a range of topics – such as American and Scandinavian History – were explored. Despite this progress in examining different regions, most of the papers were still heavy on questions about political and military history, and this was also the case with the papers that explored non-European histories. However, in terms of the actual number of questions asking about these topics, the numbers had gone down. In the papers from 1905 an average of 61% of the paper was about political history and 25% was on military history; in 1975 the averages were 36% political and 23% military history. This is a fairly significant decrease in political history and it is mirrored by the rise in more open-ended or nuanced questions, asking students to discuss lengthy statements or explain the factors behind complicated events, such as the failure of crusades in the thirteenth century. There were also questions that involved aspects of social and cultural history, including a question on the possibility of a twelfth century renaissance or a question on the effectiveness of pastoral care in the Old English Church.

I mentioned earlier that there were also a new range of smaller and focused honours classes and many of these wouldn’t look out of place in a history course catalogue today. In Modern History there were a range of these classes, including: ‘The Rise and Fall of Personal Monarchy’, ‘Anglo-French Maritime Rivalry’, ‘The American Revolution’, ‘The Age of Peterloo’ and ‘The Diplomatic Prelude to the Second World War’. Some of these classes represent a divergence from the high politics dominated classes of the previous decades. The class ‘The Development of British Urban Society in the 19th Century’ in particular explores a group of people who had been neglected in the curriculum until this time, reflecting a newfound interest in studying the history of those who were marginalised and overwhelmingly excluded from politics.

This was also the case with Medieval History, which boasted a great range of interesting new modules, including: ‘Scandinavia and Northern Europe’, ‘Art and Society in the Middle Ages’, The Decline of Moorish Spain’, ‘Learning and Art at the Court of Charlemagne and his Sons’, ‘British Castles’, ‘English Towns in the Later Middle Ages’, and ‘The Italian Renaissance’. The cultural history aspects of classes on art, society and the renaissance would have been plentiful, and the number of non-Western areas being covered had also increased. Most interestingly, there was a paper for the class ‘Harun Al-Rashid’, the first Abbasid Caliph. The inclusion of Islamic History is entirely new, and suggests that there was indeed a thirst among students to study the often-abandoned histories of societies outside of Europe.

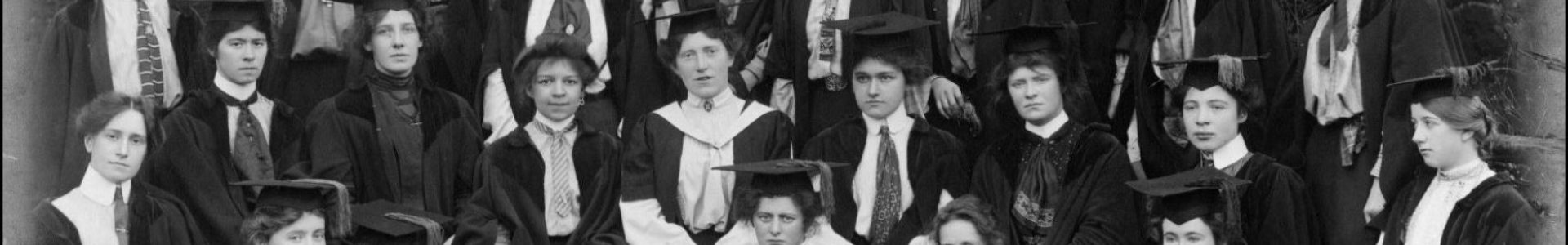

This considerable range of modules is indicative of an increase in the number of staff and students. To deliver this many classes there would have needed to be a higher number of staff members, all with their own areas of speciality, and an increased number of students to take them. This is backed up by the graduate data, which tells us that there were 17 honours history graduates in 1955 and 59 honours history graduates in 1975. This considerable increase in students can be credited with the new range in classes to take, as can the strides that were made in social equality between 1955 and 1975. It is fascinating to examine how much the examinations, and therefore the experience of studying history, had changed in twenty short years, and these changes would increase in the next two decades.

Sources

- 1975 Medieval European History Examination – ms38977/6/1/1/1/10

- 1975 Modern British History Examination – ms38977/6/1/1/1/10

- 1975 Medieval English Church History -ms38977/6/1/1/1/10

This post was written in 2021 by Amanda Stewart, who was then going into her third year of studying History at the University of St Andrews.

This post is part of a collection examining the establishment of the History degree at St Andrews, looking at the increasing number of staff and students and the gender balance of those graduating with a degree in history. You can also learn about the progression of the history degree in the twentieth century or the or the first joint honours in History. To learn more about the past paper exams from key decades throughout the twentieth century, follow these links: 1905 Past Paper, 1950s Past Paper, and 1980s/90s Past Paper, and the style and format of past papers.