Elizabeth G.K. Hewat (1895-1968)

In 1933, Elizabeth Glendinning Kirkwood Hewat quoted from the Book of Proverbs: ‘Wisdom is the principal thing; therefore get wisdom’.[1] She was, perhaps, referring to a definition of wisdom other than ‘sage advice’. In fact, she may have been alluding to her own philosophy of life, or rather, of study: her obvious zest for learning.

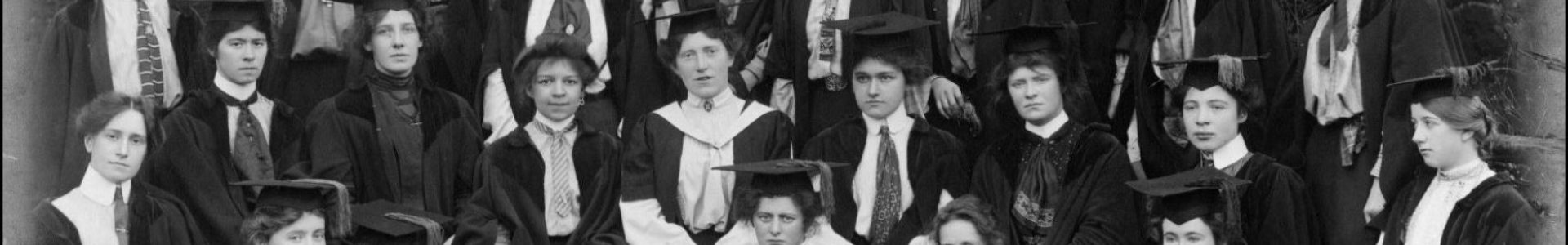

Photograph: ‘New College, Edinburgh, Winter Session, 1924-1925’, AA1.8.2-1925, New College Library, University of Edinburgh

Elizabeth Hewat’s brief connection with the University of St Andrews began in September 1919, when she was appointed – on the recommendation of history Lecturer J.D. Mackie – as an Assistant Lecturer in the history department for that academic year and on a salary of £200 per annum. She was therefore, to the best of our knowledge, the second woman to teach history at St Andrews, following directly in the footsteps of Janet Low, who had been employed as a Temporary Lecturer to cover war absences between 1917 to 1919. Hewat may have taught Edith MacQueen (then a second-year undergraduate) and Edith Thomson (then a first-year).

Hewat held a history and philosophy degree, with a first-class in the history component, from the University of Edinburgh, and she would return there for further study.[2] We are not quite sure how long Hewat stayed at St Andrews: there is no further mention of her after the official record of her appointment for the academic year 1919-1920; and we know she was studying in Edinburgh by 1922. She was one of the earliest women to graduate with a divinity degree in Scotland, and she spent her life as a missionary and a scholar in China, India and Edinburgh.

Elizabeth G.K. Hewat had been born on 16 September 1895 in Ayrshire’s Prestwick. Educated at Wellington College in nearby Ayr, her mother was Elizabeth Glendinning and her father was Kirkwood Hewat, a United Free Church of Scotland (UFC) minister.[3] As Callum G. Brown has argued, it was not until 1963, or to quote Philip Larkin’s ‘Annus Mirabilis’, ‘Between the end of the Chatterley ban/And the Beatles’ first LP’, that church-going would begin to substantially decline in Scotland and in Britain more widely.[4] Going to church on a Sunday, then, was still a large part of life in Scotland from the end of the nineteenth century until the middle years of the twentieth century.

Elizabeth G.K. Hewat (centre)

Photograph: ‘New College, Edinburgh, Winter Session, 1924-1925’, AA1.8.2-1925, New College Library, University of Edinburgh

Hewat was a ‘daughter of the manse’, and so would have grown up with a very good understanding of the life of a minister. Following her time teaching history at the University of St Andrews, Hewat began reading theology at the University of Edinburgh’s New College in 1922, and she also began teaching at the UFC Women’s Missionary College. Four years later, she became the first woman to graduate with a Bachelor of Divinity from the University of Edinburgh and, in theory, the right to become a minister herself. Frances Melville had been the first woman to be awarded a BD in Scotland, having graduated from the University of St Andrews’ St Mary’s College in 1910, while Olive Winchester graduated with a BD from the University of Glasgow in 1912.

Refusing to hide her light under a bushel, Hewat felt a calling for ministry; however, there was no precedent for female ministry in Scotland.[5] Hewat’s entry in The New Biographical Dictionary of Scottish Women explains that, ‘Her case led to a debate on women’s ordination during the 1926 UFC General Assembly. The proposer argued that she had come top of her class, making it difficult to argue that she could not be put on the same level as the men.’[6] Hewat did not win her case, but seeds had been sown that would be reaped around forty-two years later.

Following the debate, Hewat left Scotland for China as planned anyway; although she had hoped to out missionary work as an ordained minister abroad, she ‘combined work as a teaching missionary with scholarly research comparing Hebrew and Confucian Wisdom literature.’[7] She then returned to Scotland once more, and began to study for a doctorate in Divinity at Edinburgh’s New College; she graduated with her doctorate, the thesis of which was entitled ‘A Comparison of Hebrew and Chinese Wisdom, as Exemplified in the Book of Proverbs and the Analects of Confucius’, in 1934.

Whilst pursuing her doctoral research, Hewat also undertook voluntary work at Edinburgh’s North Merchiston Church, and she was a co-founder of this church’s Fellowship of Equal Service.[8] Since 1929, the UFC had been united with the established church in Scotland, forming the Church of Scotland. Following the completion of her PhD, Hewat moved to India. In 1935, she was appointed Professor of History at Wilson College in Bombay, now Mumbai, and she was also an editorial assistant for the International Review of Missions.[9] She remained a professor at Wilson College for around twenty years and, during her time in India, became an elder within the United Church of North India.[10]

When Hewat returned to Edinburgh during the second half of the 1950s, she became active within both academia and church life in Scotland, continuing her activism for female ministry, while also now supporting the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament. Back in Edinburgh, Hewat was appointed National Vice-President of the Women’s Guild, and she was also awarded an honorary Doctor of Divinity from her alma mater. Hewat penned numerous essays and books, including the first official history of missions undertaken by the Church of Scotland, which was published in 1960, and her own guide to meditation, which was entitled Thine Own Secret Stair: Suggestions for a Month’s Private Prayer and which was still being printed until at least the beginning of the 1980s.[11]

During the 1960s, Hewat supported the successful campaign for women’s ordination within the Church of Scotland. Reflecting upon this time fifty years later in Life and Work, the Church of Scotland’s magazine, the Rev Dr Margaret Forrester, one of the Church of Scotland’s first female ministers, recalled as a student meeting Hewat in Orkney during the evangelism of the ‘Tell Scotland Movement’.[12] Forrester emphasised that Hewat was a pioneer, paving the way for the success of the campaign for female candidates for ministry within the Church of Scotland during the 1960s:

Fifty years on we celebrate a collegiality of women ministers. No one is first. No one stands alone. Elizabeth Hewat represents those who blazed the trail. Mary Lusk petitioned the General Assembly. Catherine McConnachie was the first woman to be ordained as a minister in the Church of Scotland. Effie Irvine was the first to be called to a parish. Jean Montgomerie was the first to be convener of an Assembly committee. Sheilagh Kesting was the first minister to be Moderator of the General Assembly. Lorna Hood was the first serving parish minister to be Moderator of the General Assembly.[13]

The Moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland is appointed for one year’s service, and this year the Moderator has been the Rt Rev Sally Foster-Fulton. In September 2023, the Moderator visited the University of St Andrews, making a return visit during the Eastertide of 2024. On the Tuesday of her week-long visit to Fife in 2023, Fife Today reported that the Moderator would ‘tour the University of St Andrews Eden Campus at Guardbridge before visiting the university’s chaplain’s house’ and then

On Wednesday, after morning prayers in Culross Abbey, the Moderator will set out in a group on the Pilgrim Way. The group will have a picnic lunch at Cairneyhill Church before continuing the route to Dunfermline. There will then be an evening service at Abbotshall Church, Kirkcaldy, where the Scratch Pilgrim Choir will be participating under leadership of Richard Michael, church organist and visiting Professor of Jazz at the University of St Andrews.[14]

It is poignant that, almost one hundred years after Elizabeth G.K. Hewat petitioned the UFC General Assembly, a female Moderator of the General Assembly visited the place where Hewat had begun her academic teaching career, as one of the first female Assistant Lecturers in history.

By Dr Sarah Leith. Sarah is an historian of environmental thought, literature and culture in twentieth-century Scotland and she is currently a Research Assistant for the Women Historians of St Andrews project.

[1] Proverbs 4:7 in Elizabeth Glendinning Kirkwood Hewat, ‘Elizabeth Glendinning Kirkwood Hewat, ‘A Comparison of Hebrew and Chinese Wisdom, as Exemplified in the Book of Proverbs and the Analects of Confucius’ (Unpublished PhD thesis, The University of Edinburgh, 1933), p.159, n.6.

[2] See ‘Elizabeth G.K. Hewat’, ‘Equality, Diversity and Inclusion’, The University of Edinburgh https://equality-diversity.ed.ac.uk/celebrating-diversity/inspiring-women/women-in-history/elizabeth-g-k-hewat [Accessed: 17 April 2024].

[3] ‘HEWAT, Elizabeth Glendinning Kirkwood’, in Elizabeth Ewen, Rose Pipes, Jane Rendall and Siân Reynolds (eds), The New Bibliographical Dictionary of Scottish Women (Edinburgh, 2017), pp.197-8, at p.198.

[4] See Philip Larkin, ‘Annus Mirabilis’, in Philip Larkin, Collected Poems ed. Anthony Thwaite (London, 1988), p.167; Callum G. Brown, The Death of Christian Britain: Understanding secularisation 1800-2000 (2nd edn., Abingdon, 2009). p.1; Callum G. Brown, The Battle for Christian Britain: Sex, Humanists ad Secularisation, 1945-1980 (Cambridge, 2019), p.21.

[5] Rev Dr Margaret Forrester, ‘50 years of women in ministry’, Life and Work (May 2018) https://digital.lifeandwork.org/articles/165720?article=18-1 [Accessed: 21 April 2024].

[6] ‘HEWAT, Elizabeth Glendinning Kirkwood’, p.198.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Elizabeth G.K. Hewat, Vision and Achievement 1796-1956: A History of the Foreign Missions of the Churches United in the Church of Scotland by Elizabeth G. K. Hewat, (Edinburgh, 1960); Elizabeth G.K. Hewat, Christ and Western India: A Study of the Growth of the Indian Church in Bombay City from 1813 (1950).

[12] Rev Dr Margaret Forrester, ‘50 years of women in ministry’, Life and Work (May 2018) https://digital.lifeandwork.org/articles/165720?article=18-1 [Accessed: 21 April 2024].

[13] Ibid.

[14] John A. MacInnes, ‘Moderator of the General Assembly unveils full schedule for week-long Fife visit’, Fife Today (21 September 2023) https://www.fifetoday.co.uk/news/people/moderator-of-the-general-assembly-unveils-full-schedule-for-week-long-fife-visit-4343775 [Accessed: 21 April 2024].